Lightweight containers provide a way to manage and locate business objects. No longer is there any need for JNDI lookups, custom service locators, or Singletons: the lightweight container provides a registry of application objects.

Lightweight containers are both less invasive and more powerful than an EJB container where co-located applications are concerned.

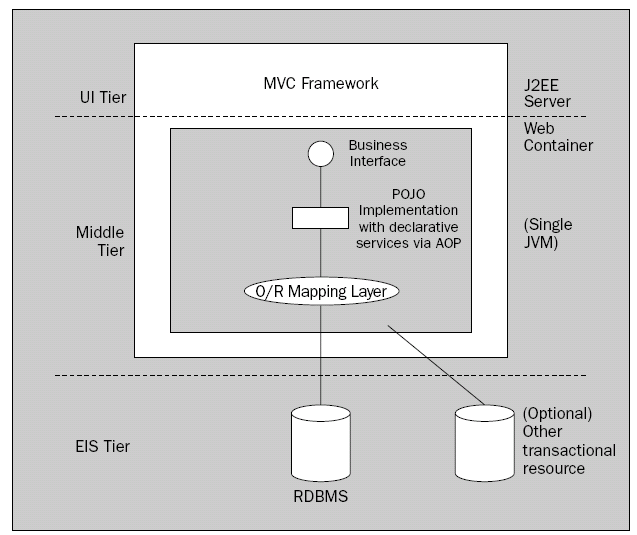

To provide a complete solution, the lightweight container must provide enterprise services such as transaction management. Typically this will invoke AOP interception: transparently weaving in additional behavior, such as transaction management, before and after the execution of business methods.

From the user’s perspective, the web tier is provided by an MVC framework. We can use a dedicated

web framework such as Struts or WebWork, or—in the case of Spring—a web tier that can itself be managed

by the lightweight container and provide close integration with business objects.

Business objects will be POJOs, running inside the lightweight container. They may be “advised” via AOP interception to deliver enterprise services. Unlike EJBs, they don't usually need to depend on container

APIs, meaning that they are also usable outside any container. Business objects should be accessed

exclusively through their interfaces, allowing pluggability of business objects without changing calling

code.

Data access will use a lightweight O/R mapping layer providing transparent persistence, or JDBC via a

simplifying abstraction layer if O/R mapping adds little value.

Strengths

Following are some of the advantages of using this architecture:

(1) A simple but powerful architecture.

(2) As with local EJBs or an ad hoc non-EJB solution, horizontal scalability can be achieved by clustering

web containers. The limitations to scalability, as with EJB, will be session state management,

if required, and the underlying database. (However, databases such as Oracle 9i RAC can

deliver huge horizontal scalability independent on the J2EE tier.)

(3) Compared to an ad hoc non-EJB architecture, using a lightweight container reduces rather than

increases complexity. We don't need to write any container-specific code; cumbersome lookup

code is eliminated. Yet lightweight containers are easier to learn and configure than an EJB

container.

(4) Sophisticated declarative services can be provided by a lightweight container with an AOP

capability. For example, Spring's declarative transaction management is more configurable than

EJB CMT.

(5) This architecture doesn't require an EJB container. With the Spring Framework, for example,

you can enjoy enterprise services such as declarative transaction management even in a basic

servlet engine. (Whether you need an application server normally depends on whether you

need distributed transactions, and hence, JTA.)

(6) Highly portable between application servers.

(7) Inversion of Control allows the lightweight container to “wire up” objects, meaning that the complexity

of resource and collaborator lookup is removed from application code, and application

objects don't need to depend on container APIs. Objects express their dependencies on collaborators

through ordinary Java JavaBean properties or constructor arguments, leaving the IoC

container to resolve them at runtime, eliminating any need for tedious-to-implement and hardto-

test lookups in application code.IoC provides excellent ability to manage fine-grained business objects.

(8) Business objects are easy to unit test outside an application server, and some integration testing

may even be possible by running the lightweight container from JUnit tests. This makes it easy

to practice test first development.

Weaknesses

Following are some of the disadvantages of using this architecture:

(1) Like a local EJB architecture, this architecture can't support remote clients without an additional

remoting facade. However, as with the local EJB architecture, this is easy enough to add, especially

if we use web services remoting (which is becoming more and more important). Only in

the case of RMI/IIOP remoting are remote EJBs preferable.

(2) There's currently no “standard” for lightweight containers comparable to the EJB specification.

However, as application objects are far less dependent on a lightweight container than EJBs are

on the EJB API, this isn't a major problem. Because application objects are plain Java objects,

with no API dependencies, lock-in to a particular framework is unlikely. There are no special

requirements on application code to standardize.

(3) This architecture is currently less familiar to developers than EJB architectures. This is a nontechnical

issue that can hamper its adoption. However, this is changing rapidly.

Implementation Issues

Following are some of the implementation issues you might encounter:

(1) Declarative enterprise services can be provided by POJOs using AOP, thus taking one of the best

features of EJB and applying it without most of the complexity of EJB.

(2) A good lightweight container such as Spring can provide the ability to scale down as well as up.

For example, Spring can provide declarative transaction management for a single database

using JDBC connections, without the use of JTA. Yet the same code can run unchanged in a different

Spring configuration taking advantage of JTA if necessary.

(3) A nice variation is ensuring that POJO business objects can be replaced by local EJBs without

changes in calling code. Spring provides this ability: all we need to do is create a local EJB with

a component interface that extends the business interface, if we wish to use EJB. These last two

points make this approach highly flexible, if requirements change. (This results largely from

good OO programming practice and the emphasis on interfaces.)